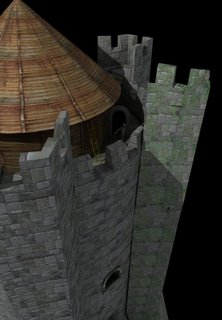

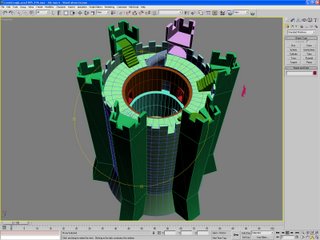

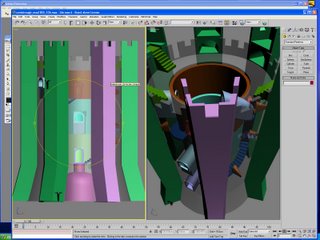

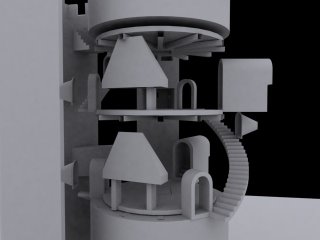

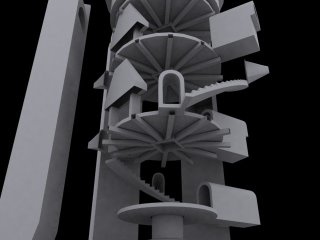

First up is a birds eye straight from Max then a few views with xray on to see the spiral staircases and recesses etc.

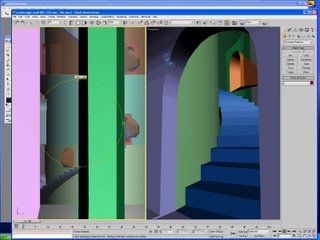

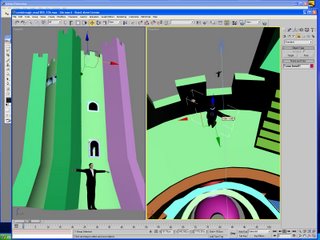

A few light-tracer renders and then some attempts at texturing the castle.

Concept for 3D viz of Conisbrough castle

The images and animations on the CD show off the potential for this visualisation proposal.

Making use of 3D graphics with virtual cameras and the ability to display photo-realistic renderings gives the viewer who may be unable to visit the real site for one reason or another at least a sense of the scale and environment of the structure. With the ability to visualise camera flyby’s from ground to flagpole and trips up the spiral stairs and perhaps a bucket eye view from well floor to keep roof there are views that even real visitors would never see. Throw into this mix control over lighting and even seasonal changes – imagine watching the progression of shadows as the castle is seen bathed in early morning June sunlight through to sunset in late evening all in 60 seconds!

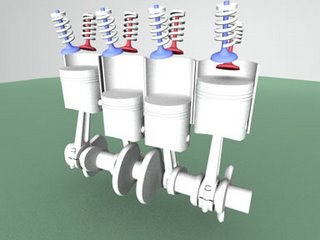

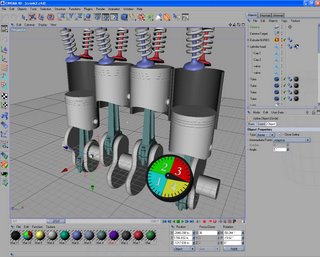

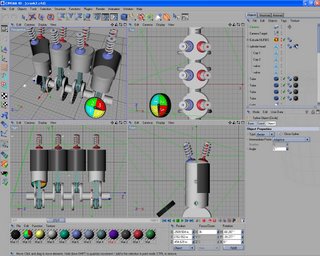

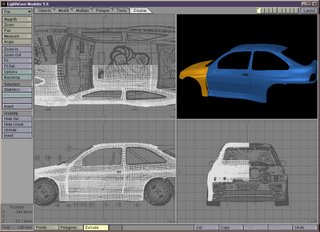

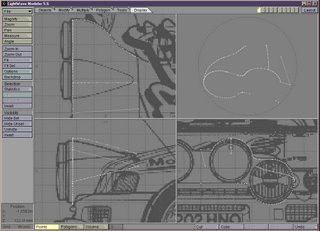

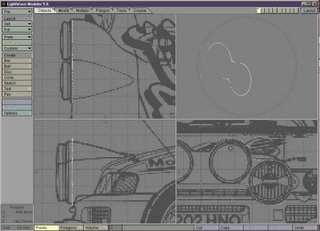

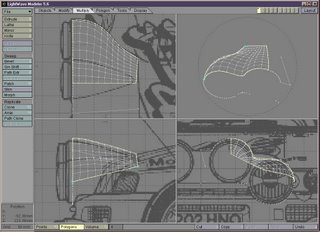

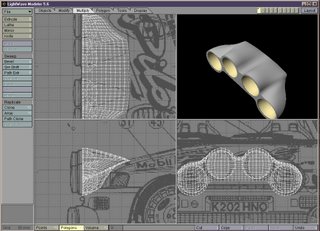

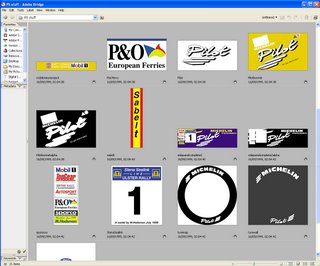

I wanted to show at least the possibilities with some renderings of other structures (a few churches and real world street scenes) as well as some of the Conisbrough keep. I have included an un-textured keep showing how its possible to display cut-out or x-ray views of the internal structure; some shots of a typical texturing method which shows at this stage very clean looking textures! And typical flybys of how it’s possible to have complete control over lights and cameras.

I hope this goes some way to showing the potential. With that said it would be useful if you could contribute what you’d expect from such a system and how you would envisage it working i.e. Using touch panel screens with multimedia presentations or purely still images used as historical teaching support. I have some ideas that I have imagined from the beginning:-

1. User interactivity. The ability to initiate animations; listen to audio clips; control lighting etc

2. A slideshow of pre-rendered photo-realistic images showing castle and keep.

3. An artist’s impression of how the construction progressed.

4. Overlays of the castle in 11th and 21st centuries, showing how much or how little it has deteriorated.

When I initially thought of this concept I looked at Thornton Abbey and imagined how it might be re-constructed back to its former glory given what is still remaining now. I don’t know whether that is too ambitious given the intricate craftsmanship involved or indeed whether there is enough information in the archives to make a worthy guess That is why I think Conisbrough castle’s condition makes this idea a more realistic goal I believe.

M.Hodsman 2004